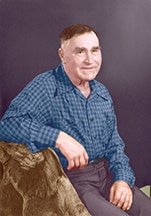

Albert & Julia: A Philosophy of Hands-On Giving

Albert Haller was born in Port Angeles to Sequim Valley pioneers Max and Anna Haller. The tenth of thirteen children, Albert began working in the woods at an early age. His career in logging began in the era of horses and continued through steam donkeys and caterpillar tractors to the modern technology of the late 20th century.

Albert Haller was born in Port Angeles to Sequim Valley pioneers Max and Anna Haller. The tenth of thirteen children, Albert began working in the woods at an early age. His career in logging began in the era of horses and continued through steam donkeys and caterpillar tractors to the modern technology of the late 20th century.

Albert began selective logging in the Lost Mountain district in 1937 and built a reputation as a careful, competent logger. “He out-conserves the conservation policies of the Forest Service,” said then-USFS Supervisor Carl Neal. “We never worry when Albert Haller is logging inside the Olympic National Forest.”

Albert and his wife, Julia (Tomaski Guger) were both largely self-educated. Their formal schooling ceased after fourth grade and they were both on their own by the age of twelve. Their marriage was a true partnership. Julia participated in the decision-making and management of the logging business. She and their three children were often called upon to help with logging operations in the early years.

Albert and his wife, Julia (Tomaski Guger) were both largely self-educated. Their formal schooling ceased after fourth grade and they were both on their own by the age of twelve. Their marriage was a true partnership. Julia participated in the decision-making and management of the logging business. She and their three children were often called upon to help with logging operations in the early years.

A family garden provided much of their food. Both Albert and Julia enjoyed fishing, and their boys were avid hunters. Theirs was a life of frugality and self-reliance, and in the beginning, a struggle financially.

With Julia’s support, Albert began buying land instead of simply buying stumpage. He expanded his log sales beyond the Olympic Peninsula, which resulted in better prices. At one time, Albert was the largest independent land owner in Clallam County, outranked only by the large timber companies. The logging company was disbanded shortly after Julia’s death in 1954, and Albert turned to land development. He was working on the Dungeness Heights development at the time of his death in 1992 at age 88.

(The following is excerpted with permission from the Clallam County Historical Society’s newsletter, August 2016, by John Kendall:)

Unlike most loggers who bought timber rights, logged the land, then moved on, Haller bought the land to be logged. He “treated trees as a crop, and when logging was done, seedlings were planted,” said Judy Reandeau Stipe, executive director of the Sequim Museum. He became the largest private landowner in the county.

On occasion, when he got his tax bills, he went to the county assessor’s office with an axe slung over his shoulder, and asked them to lower taxes on a particular parcel,” recalled Stipe. “Those in the office told him, ‘Mr. Haller, go home and pay your taxes.’ He would discuss it with his wife, Julia, and they took some parcels off the tax rolls and gave the land away – to churches and other non-profits.

“Apparently banks turned him down for loans in the early years of his business career, so he distrusted banks and would tell people he met, ‘If you get turned down at a bank, come and talk to me.’ He lent many people money, and from what I understand no one stiffed him.

“For new employees, down on their luck, he set up credit accounts at the Carlsborg Store and Clallam Co-op for gas and groceries, so the man could get to work and feed his family until the first paycheck arrived. I don’t know of anyone else who did it the way Albert did.”

Albert’s will reflected these early challenges, which evolved into a lasting concern for his neighbors and fellow county residents. He designated $9.2 million of his estate to the Foundation to be used for the charitable purposes dearest to his heart. His legacy lives on in the lives he has touched with his generosity.